Under Trump, Puerto Rico's Dependence on the U.S. Is a Ticking Time Bomb

There's never been a better, or more urgent time, to think about Puerto Rico's independence.

In the frenzy and furor over the Trump administration’s aggressive moves to cut spending, few have stopped to consider the impact on some of the most vulnerable recipients of federal funding: the people of America’s territories. But just a few months into Trump’s second term in office, his administration and Republicans in Congress have already frozen, cut, or threatened to eliminate billions of dollars for Puerto Rico.

The cuts began on day one, when Trump froze portions of the Inflation Reduction Act and other Biden-era climate change and infrastructure legislation, which had allocated over $3 billion to Puerto Rico.

Since then, the hits have kept on coming: $400 million for Puerto Rico’s Department of Education; $45 million in COVID-19 mitigation and vaccine funding; $17 million for addiction and mental health services; millions more in FEMA hazard mitigation funding. That’s just what we know about, and is surely an incomplete list.

It will surely get worse before it gets better. Trump hopes to dismantle FEMA entirely, while more than $11 billion earmarked for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction after Hurricane María and other recent natural disasters is still pending the agency’s approval. He claims the U.S. government will instead send disaster relief money directly to states. But how much money, exactly, would Trump and Elon Musk think it appropriate to send to a “floating island of garbage”?

Now Trump and his Republican Congress plan to cut hundreds of billions from Medicaid. That program is already critically underfunded in Puerto Rico, where the median household income is about $26,000 per year, and over 40% of the population lives under the federal poverty line.

All of this was predictable, but that makes it no less troubling. It is the result of the Trump administration’s extreme right-wing vision for the U.S. government. But it also highlights—as Trump’s abuse and neglect of Puerto Rico after Hurricane María did during his first term—the precarity of Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. colony.

Most of these spending cuts and freezes do not (yet) specifically target Puerto Rico, but island residents are particularly vulnerable to them in three key ways.

First: because the United States government has almost unlimited power over Puerto Rico, including the power to deny Puerto Ricans the rights and resources owed to Americans on the mainland, and to essentially discriminate against the island when it comes to federal funding.

That is how Medicaid and food assistance are funded at lower rates in Puerto Rico in the first place, or why Congress can decide, and the Supreme Court can uphold, that Puerto Ricans are ineligible for programs like Supplemental Security Income. And it’s why Congress and the Trump administration will potentially have much more legal leeway to cut funding to the island.

Second: Puerto Ricans are politically powerless to oppose these cuts. Whether it is an effective means of resistance or not, Democratic leaders are telling the American people to call their members of Congress and hold them to account or push them to take action. But who are Puerto Ricans going to call? Island residents send a single non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives who is functionally impotent in Washington, D.C.

Moreover, while it’s arguably counterproductive to berate American voters for their choices at the ballot box, the fact remains that they are experiencing the consequences of an election and a political system in which they are full participants. The same cannot be said of Puerto Ricans, who cannot vote for the U.S. president and are reduced to being passive subjects of Trump’s dictatorial whims.

Third: Puerto Rico is uniquely vulnerable to these actions by the Trump administration because the island is extraordinarily dependent on federal outlays, which totaled $36 billion in 2024. That is partly a failure of successive pro-statehood and pro-Commonwealth (the euphemistic term for the colonial status quo) Puerto Rican governments, who have made that reliance on federal funding the foundation of their economic policies for Puerto Rico.

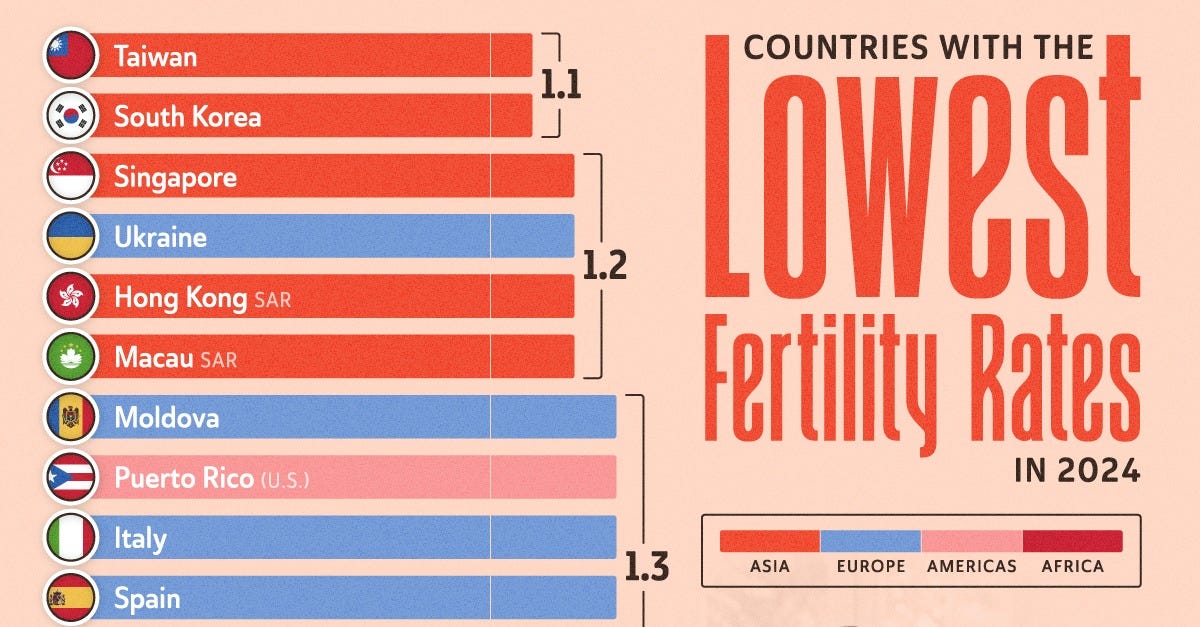

That strategy has unequivocally failed. The island is twice as poor as the poorest U.S. state; has staggering levels of wealth inequality; suffers from crumbling infrastructure, education, and healthcare; and, as a result, is mired in a deep demographic crisis driven by both outmigration and by one of the lowest birth rates in the world.

The local failures that have led to that state of affairs are significant, but they are not solely of Puerto Ricans’ own making. It bears repeating that the island is a colony of the United States; that is not an ideological claim, but a legal and political fact acknowledged by the Supreme Court. Colonies are, almost by definition, not designed to be economically successful and sustainable except to the benefit of the colonizer.

Indeed, while the U.S. government does send tens of billions of dollars to Puerto Rico, American corporations profit even more from Puerto Rican labor, the municipal bond market, tax breaks and incentives, a largely captive market for American products, and a near-monopoly on maritime trade that strangles the Puerto Rican economy while subsidizing U.S. shipping companies.

In short, Puerto Rico’s colonial status imposes a series of legal, political, and financial constraints that have prevented the island from developing a just and sustainable economy. That has aided and abetted an overreliance on federal funding that now, under President Trump, may prove disastrous.

What can be done? In the short term, unfortunately, very little. Puerto Ricans will have to hope that legal challenges to the worst of President Trump’s actions are ultimately successful, and that they include the U.S. territories despite our separate-and-unequal political subordination. But if and when the cuts start coming via federal legislation, Puerto Ricans will have to just grin and bear it, and do our best to adapt and overcome.

It may be tempting for some to think that, once Democrats are back in power, everything will be all right again. But Puerto Rico has hardly been “all right” in recent decades, and the abysmal socioeconomic conditions detailed earlier have festered under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

In fact, it was President Obama and a Democratic Congress who established a fiscal oversight board in Puerto Rico, which has instituted punitive austerity measures and deepened the island’s crises. It was President Biden who instructed his Justice Department to defend Puerto Rico’s exclusion from the Supplemental Security Income program at the Supreme Court, and under whose presidency aid from FEMA remained hopelessly delayed.

But even if Democratic presidents were extraordinary champions for Puerto Rico, Americans cannot ask the island’s residents to essentially play Russian Roulette every time there’s an election in the United States. Will the chamber be empty, which at best might preserve a wholly inadequate status quo? Or will Puerto Ricans have to bite the bullet of being ruled by a U.S. president who has the ability and the inclination to destroy our economy with the stroke of a pen—not to mention enact an anti-Latino agenda that is dangerous to Puerto Ricans on the island and the mainland?

Ultimately, the economic dependence that has placed Puerto Rico at Trump's mercy is a product of its political dependence, and Puerto Rico’s 126-year-old-and-counting colonial status must end.

How might it end? Statehood remains a no-go in Congress, which would have to approve it. Republicans are dead set against it, and Democrats are too divided on it to overcome massive GOP opposition. Indeed, despite the occasional talking points about “equality” for Puerto Ricans, they have never even really tried.

It’s reasonable to ask how sovereignty—whether full independence or sovereignty in free association with the United States—could be a feasible solution. How can one denounce that Trump’s cuts to federal funding in Puerto Rico may prove catastrophic and still argue for independence, which would mean the end of federal support for Puerto Rico altogether?

One answer is that, faced with the impossibility of statehood and the immorality of the colonial status quo, sovereignty is simply the only other option. And while, historically, only a small minority of Puerto Ricans supported it, in last year’s referendum more than 40% of voters backed a sovereign status option.

Another answer is that Puerto Rican independence would most likely not mean the immediate loss of all federal funding to the island and its people. For one thing, two-thirds of that $36 billion in 2024 federal funding to Puerto Rico was made up of direct payments through Social Security, Medicare, and Veterans’ Affairs programs. These are benefits that Puerto Ricans have earned and paid for through payroll taxes or through their military service, and that they would not lose after independence.

The Puerto Rico Status Act, which outlined a framework for resolving Puerto Rico’s status and passed the House of Representatives in 2022, made it clear that these payments would not be interrupted after Puerto Rico transitions to a sovereign status.

That legislation also proposed that Puerto Rico continue to receive full federal funding in the form of block grants for 10 years after independence, and additional funding that tapers off at a rate of 10% per year for another decade. It’s fair to question whether such a stipulation would survive the inevitable negotiations as part of any Puerto Rican decolonization process. But it underscores what Puerto Rican independence advocates and allies in Congress have argued for decades: that there would likely be a long transition period that allows Puerto Rico to wean itself off federal funding, and set up or strengthen its own social assistance programs and institutions.

Eventually, the federal funding would end. But independence would not just take away benefits, it would also give Puerto Rico political and economic power. Right now, the island cannot control its monetary and fiscal policy, set duties and tariffs, freely sign trade agreements, establish customs and immigration laws, or free itself of punitive regulations like the Jones Act. These are the tools of both sovereignty and of economic development, without which Puerto Rico has been unable to craft a sustainable and thriving economy.

Historically, those tools have worked: in a landmark study on the potential impact of changing Puerto Rico’s status, economist José Caraballo Cueto examines other 20th century post-colonial periods and concludes: “With the exception of Gabon, all former colonies that had relative GDP per capita levels similar to Puerto Rico’s at the time of independence now have relatively high GDP per capita levels.”

What the Trump administration’s cuts might do to Puerto Rico is the equivalent of having the chair you’re sitting on suddenly and violently kicked out from under you. Independence might allow Puerto Ricans to stay seated, grab wood and nails to build our own chair, and eventually take that seat of our own making, which no U.S. president could rip away from us.

It is admittedly counterintuitive to imagine that small, poor, and vulnerable Puerto Rico might be better off economically without the richest country in the world than as part of it. But the Trump presidency, which presents a clear and present danger to Puerto Ricans, should compel us to examine old assumptions and consider what seem like unlikely alternatives.

Ultimately, the case for Puerto Rican sovereignty is about more than economics: it is about redressing a profound undemocratic injustice. But it is also about preventing the present and future harm that Trump or his successors may visit on Puerto Rico as long as it remains one of America’s forgotten and wretched colonies.